12-Dec-2013 • Chris C.

The threat of agricultural bioterrorism remains one of the single greatest threats to local and state economies, as well as the overall U.S. economy. In worst case scenarios, specific vulnerabilities could be exploited by highly capable actors which would extend damage beyond far-reaching economic losses, and threaten broader domestic food security and continuity. While not entirely dismissed, the threat of agricultural bioterrorism has not received sufficient or enough consistent attention in comparison to lower probability threats. Having garnered periodic spurts of attention in the past fifteen years, academic reports and publications on the subject are currently waning. In fact, very little has been published publicly on the subject of agricultural bioterrorism in the past six years, and much of what was written prior to the current lull relied on information and data that is now ten or more years out-of-date. As such, there is a need for a current review and analysis of antiterrorism efforts to protect agriculture, as well as a present-day look at the threat environment. This threat assessment will bridge the gap in agricultural bioterrorism scholarship while hopefully spurring a wider and more routine discussion on the subject.

The greatest threat to the U.S. agriculture industry is the intentional introduction of Foot-and-mouth disease by domestic or foreign terrorists. Livestock auctions are particularly vulnerable. Inoculated livestock could end up in many different ranches and farms across different states before symptoms would manifest. Billions of dollars of lost exports and culled livestock would be the short-term consequence. Long-term consequences could be more devastating. Pre-harvest crops are also quite vulnerable to attack. Crop pathogens that impact corn, soybeans, wheat, and other cereals are a significant threat. Farms are quite vulnerable to attack given their size, number of potential avenues for attack, and lack of security. Surveillance and the early stemming of outbreaks following a terrorist attack would be critical to mitigating loss. While genetic hardening has reduced the likelihood of natural outbreaks, it has made crops particularly vulnerable to intentional introduction of disease. Export crops and staple grains are prime targets.

The majority of the statistics and information about agriculture in this paper are taken from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Other government reports and documents were also consulted. While this assessment attempts to offer policy makers a more current threat assessment on the subject of agricultural bioterrorism, this paper is by no means comprehensive. Rather, it takes a cursory look at the subject and offers conclusions and recommendations based on surficial information.

This paper does not extend beyond biological means of agricultural terrorism, however, there exist other means to effectively target the U.S. Despite this fact, it is the opinion of the author that the threat of agricultural bioterrorism remains the gravest threat to U.S. agriculture. The agriculture industry in the U.S. not only feeds Americans, but people around the world through U.S. agricultural exports. The continuity of the U.S. agriculture industry is vital not only to U.S. national security, but also to global food security as a major exporter of agricultural goods.

This paper is broken up into several parts. First, the paper will illuminate the impact of agriculture and the agricultural industry on the U.S. economy and on national security. Then it will put forth a working definition of agricultural bioterrorism and illustrate existing responsibilities (i.e., which organizations are currently tasked with protecting the U.S. from agroterrorism), policies, and procedures as they pertain to the threat. Next, a vulnerability analysis will highlight specific targets and their level of vulnerability. From there, a threat analysis will list potential perpetrators and their propensity for carrying-out acts of agricultural bioterrorism. Lastly, recommendations will be made based on the findings of the preceding sections, and concluding remarks will be given to form an overall assessment of the threat of agricultural bioterrorism.

Agriculture and agriculture related industries make up 4.8 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), or $742.6 billion.1 As a contributing factor, farms compose $138.7 billion of that figure, and constitute about 1 percent of the overall GDP.2 In raw numbers, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported the agriculture industry bringing in $419.4 billion in gross income for 2011 while incurring $321.3 billion in production related expenses for an industry-wide net income of $98.1 billion.3 Projected net income for the agriculture industry in 2013 is $120.6 billion.4 Agricultural exports accounted for $135.77 billion in 2012.5 Of principal agricultural exports, the U.S. represented 8.9 percent of wheat, 44.7 percent of corn, 27.7 percent of cotton, 8.6 percent of rice, and 39.5 percent of oilseed (soybean) exports worldwide.6

| Export | Percentage of Worldwide Exports |

|---|---|

| Wheat | 18.90% |

| Corn | 44.70% |

| Cotton | 27.70% |

| Rice | 8.60% |

| Oilseed (Soybean) | 39.50% |

| Source: “Agriculture Statistics 2012,” USDA, 2012, accessed November 13, 2013, http://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Ag_Statistics/2012/2012_Final.pdf. |

Domestically, there are numerous industries that are dependent upon agriculture related inputs. These include: forestry, fishing, and related activities; food, beverages, and tobacco producers; textiles, apparel, and leather producers; as well as food services and drinking businesses.7 Together these dependent industries makeup $603.9 billion of the U.S. economy.8 Other industries that impact and are impacted by the agriculture industry are: the gasoline and fuel, fertilizer, seed, feed, and livestock industries which represent $16.9 billion, $27.6 billion, $17.6 billion, $57 billion, and $23.5 billion respectively, and $142.6 billion collectively in agriculture related expenses.9

Labor statistics from the most recent Census of Agriculture show that the agricultural industry spent $21.9 billion in 2007 on labor.10 From that, the agriculture industry employs over 2.6 million workers.11 Agriculture dependent industries employ another 13.5 million workers.12 Cumulatively, there are more than 16 million agriculture and agriculture-dependent jobs making up 9.1 percent of total U.S. employment.13

| Industry | Percentage of Annual Labor Expenditures | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Greenhouse, nursery, floriculture operations | 21% | $4.7b |

| Fruit and tree nut operations | 16% | $3.5b |

| Dairy cattle and milk production | 13% | $2.8b |

| Vegetable and melon farms | 10% | $2.2b |

| Oilseed and grain farms | 10% | $2.1b |

| Beef cattle farms | 7% | $1.5b |

| Animal aquaculture and other animals, poultry and eggs, hogs and pigs, cattle feedlots, and sheep and goats | 23% | $5.1b |

| Source: “2007 Census of Agriculture: Farm Labor,” USDA, last modified January 30, 2012, accessed November 10, 2013, http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2007/Online_Highlights/Fact_Sheets/Economics/farm_labor.pdf. |

Nine states jointly represent over half of all agriculture related employment.14 Nearly 450,000 people are in employed in California alone. Washington state employs approximately 240,000 workers, while Texas, Florida, Oregon, Michigan, North Carolina, Minnesota and Wisconsin each employ more than 75,000 ag-workers.15

| State | Market Value of Agricultural Products Sold and Government Payments |

|---|---|

| California | $34.1b |

| Texas | $21.7b |

| Iowa | $21.1b |

| Nebraska | $15.9b |

| Kansas | $14.8b |

| Illinois | $13.8b |

| Minnesota | $13.6b |

| North Carolina | $10.5b |

| Wisconsin | $9.2b |

| Source: “Table 838. Farms–Number, Acreage, and Value by State: 2002 and 2007,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2012, accessed November 12, 2013, http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2012/tables/12s0838.pdf. |

Of the 920 million acres of farmland which spans across all fifty states, nine states represent over half of the total market value of agricultural products sold and government payments made in the U.S.16 California ($34.1 billion), Texas ($21.7 billion), Iowa ($21.1 billion), Nebraska ($15.9 billion), Kansas ($14.8 billion), Illinois ($13.8 billion), Minnesota ($13.6 billion), North Carolina ($10.5 billion), and Wisconsin ($9.2 billion) represent over $150 billion.17 Similarly, nine states make up over half of the total value of land and buildings in the agriculture industry. Texas, California, Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Nebraska, Missouri, Indiana, and Wisconsin constitute 52 percent or $996.1 billion of the $1.9 trillion of land and buildings held by the agricultural industry.18

| State | Value of Land and Buildings in the Agriculture Industry | Percentage of the Total Agriculture Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Texas | $217.8b | 11% |

| California | $170.2b | 9% |

| Iowa | $138.6b | 7% |

| Illinois | $130.8b | 7% |

| Minnesota | $80.4b | 4% |

| Nebraska | $69.3b | 4% |

| Missouri | $68.4b | 4% |

| Indiana | $63.6 | 3% |

| Wisconsin | $57b | 3% |

| Source: “Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012,” USDA, 2012, 42, accessed November 13, 2013, http://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Ag_Statistics/2012/chapter09.pdf. |

The agricultural output of the U.S. agriculture industry is equally impressive. In terms of livestock, in the U.S. there are 90.8 million head of cattle, 66.4 million hogs and pigs, 5.3 million sheep and lambs valued at $100.7 billion, $8.1 billion, and $1.2 billion respectively.19 Six states represent 52 percent of the two billion bushels U.S. wheat production worth $14.4 billion.20 Arkansas and California make up sixty-eight percent of the 185 million hundredweight worth of U.S. rice production totalling $2.6 billion.21 Four states constitute fifty-seven percent of the 12.4 billion bushels of corn production valued at $76.5 billion.22 214.4 billion bushels of sorghum worth $1.3 billion is grown in 14 states.23 Fifty-one percent of that production occurs in Kansas alone.24 The Cotton industry, worth $7.3 billion, produces 16 billion metric tons.25 Tobacco, which is only grown in ten states, has over seventy percent of its 601 million pounds of production done in North Carolina and Kentucky.26 Fifty-four percent of soybean production is in Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Indiana.27 Seven states make up fifty-seven percent of the $1.7 billion worth of chicken production.28 The U.S. also makes up a third of all exported poultry, meat, and broiler products worldwide.29 The 8.6 billion broilers alone are worth $23.2 billion.30 Additionally, the U.S. exports nearly half of the world’s turkey exports, valued at $5 billion.31 One third of the nation’s $39.7 billion milk production occurs in California and Wisconsin.32

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | |||

| Top Producing States (33% of Total Production) | |||

| Texas | 11.9m | $11.9b | |

| Nebraska | 6.45m | $8b | |

| Kansas | 6.1m | $6.8b | |

| California | 5.35m | $6.2b | |

| U.S. Total | 90.8m | $100.7b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hogs and Pigs | |||

| Top Producing States (55% of Total Production) | |||

| Iowa | 20m | $2.6b | |

| Minnesota | 6.8m | $1.1b | |

| North Carolina | 8.9m | $888m | |

| U.S. Total | 66.4m | $8b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep and Lambs | |||

| Top Producing States (39% of Total Production) | |||

| Colorado | 623,000 | $55.8m | |

| California | 465,000 | $45.7m | |

| Texas | 230,000 | $36.5m | |

| Wyoming | 230,000 | $34m | |

| U.S. Total | 5.3m | $442.9m |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | |||

| Top Producing States (57% of Total Production) | |||

| Iowa | 66.3m | $192.3m | |

| North Carolina | 19.4m | $176.1m | |

| Georgia | 24.7m | $150.7m | |

| Arkansas | 19.9m | $139.5m | |

| Alabama | 15.4m | $109.1m | |

| Pennsylvania | 28.9m | $106.9m | |

| Texas | 23.6m | $99.2m | |

| U.S. Total | 447m | $1.7b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | |||

| Top Producing States (58% of Total Production) | |||

| Minnesota | 46.5m | $799.2m | |

| North Carolina | 32m | $772.6m | |

| Arkansas | 30.5m | $411.9m | |

| Virginia | 17.5m | $313.9m | |

| South Carolina | 11.5m | $305.9m | |

| California | 15m | $287.5m | |

| U.S. Total | 249m | $5b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eggs | |||

| Top Producing States (50% of Total Production) | |||

| Iowa | 14.5b | $931.5m | |

| Pennsylvania | 7.3b | $497m | |

| Georgia | 4.3b | $491m | |

| Ohio | 7.6b | $490.6m | |

| Indiana | 6.5b | $422.3m | |

| Texas | 4.9b | $420.6m | |

| Arkansas | 3b | $406.2m | |

| U.S. Total | 91.9b | $5b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk Cows | |||

| Top Producing States (50% of Total Production) | |||

| California | 1.8m | $7.7b | |

| Wisconsin | 1.3m | $5.4b | |

| U.S. Total | 9.2m | $39.7b |

| Source: “Agricultural Statistics 2012,” USDA, 2012, accessed November 13, 2013, http://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Ag_Statistics/2012/2012_Final.pdf. |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | |||

| Top Producing States (57% of Total Production) | |||

| Iowa | 2.4b bushels | $14.5b | |

| Illinois | 1.9b bushels | $12.3b | |

| Nebraska | 1.5b bushels | $9.4b | |

| Minnesota | 1.2b bushels | $7b | |

| U.S. Total | 12.4b bushels | $75.5b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soybeans | |||

| Top Producing States (54% of Total Production) | |||

| Iowa | 466m bushels | $5.5b | |

| Illinois | 415m bushels | $5b | |

| Minnesota | 270m bushels | $3.1b | |

| Nebraska | 258m bushels | $3b | |

| Indiana | 238m bushels | $2.8b | |

| U.S. Total | 3.1b bushels | $35.8b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | |||

| Top Producing States (52% of Total Production) | |||

| Kansas | 276.5m bushels | $2b | |

| North Dakota | 199.9m bushels | $1.7b | |

| Montana | 175m bushels | $1.3b | |

| Washington | 167.9m bushels | $1.1b | |

| Idaho | 116m bushels | $786.2m | |

| South Dakota | 104.8m bushels | $799.5m | |

| U.S. Total | 2b bushels | $14.4b |

| Category | State | Quantity | Total Market Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | |||

| Top Producing States (68% of Total Production) | |||

| Arkansas | 78.1m cwt | $1.1b | |

| California | 48.4m cwt | $774.4m | |

| Louisiana | 26.4m cwt | $362.1m | |

| Texas | 12.9m cwt | $146.1m | |

| Mississippi | 10.8m cwt | $112.2m | |

| Missouri | 8.3m cwt | $182.5m | |

| U.S. Total | 185m cwt | $2.6b |

| Source: “Agricultural Statistics 2012,” USDA, 2012, accessed November 13, 2013, http://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Ag_Statistics/2012/2012_Final.pdf. |

Prior to analyzing vulnerabilities and threats, or looking at which domestic organizations have the responsibility of defending the homeland from agricultural bioterrorism, a brief discussion about redefining agroterrorism and defining agricultural bioterrorism needs to take place; given that traditional definitions of agroterrorism are problematic.

Most definitions classify agroterrorism as a subset of bioterrorism. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, bioterrorism is “the deliberate release of viruses, bacteria, or other germs (agents) used to cause illness or death in people, animals, or plants.”33 However, by placing agroterrorism solely under the classification of bioterrorism, one is defining the act in a manner that is too restrictive and unnecessarily narrows the scope of what should be considered agricultural terrorism. A commonly used definition holds that agroterrorism is “the deliberate introduction of an animal or plant disease with the goal of generating fear over the safety of food, causing economic losses, and/or undermining social stability.”34 Under this definition, agroterrorism is limited to acts of terrorism involving the intentional release of biological agents for the purpose of generating fear over food safety and/or undermining social stability. To best understand why traditional definitions of agroterrorism are unsatisfactory, it is important to break the term apart.

Broken into two terms, agroterrorism is “agro” and “terrorism.” Agro is derived from agriculture or agricultural, which is defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “the science, art, or practice of cultivating the soil, producing crops, and raising livestock and in varying degrees the preparation and marketing of the resulting products.”35 So when referring to agriculture, most would agree that the definition does not include crop production, raising livestock, and the preparation and marketing of the resulting products thereof. That said, the definition of the second term, “terrorism,” is more contentious and the subject of much debate in academic circles. Indeed, there are numerous definitions, but Dr. Jeffrey M. Bale, a historian and terrorism scholar at the Monterey Terrorism Research and Education Program at the Monterey Institute of International Studies, has arrived at a good working definition. According to Bale, terrorism is “the use or threatened use of violence, directed against victims selected for their symbolic or representative value, as a means of instilling anxiety in, transmitting one or more messages to, and thereby manipulating the attitudes and behavior of a wider target audience or audiences.”36 Using this definition, strictly, the intent of an actor or actors, is what is important in classifying something as an act of terrorism or not.

Bringing the derived definitions of “agriculture” and “terrorism” back, the error in the widely used definition of agroterrorism becomes easier to see. Sub-classifications and typologies of terrorism can be made and appropriately used, but on the basis of clearly and consistently defining who the perpetrator or perpetrators are, and/or what and/or how something is targeted; assuming that the intent behind the act satisfactorily meets the criteria laid out in the preceding definition of terrorism. The term agroterrorism does not clearly or consistently convey a meaning which excludes means of terrorism outside of biological. Rather, the traditional definition of agroterrorism more accurately describes “agricultural bioterrorism,” not agroterrorism. While the author of this paper finds that there are existential threats to the agriculture industry beyond biological, those threats pale in comparison and are therefore not included in this threat assessment. For accuracy and the purposes of this threat assessment, the term “agroterrorism” will henceforth include all means of violence against agriculture in its meaning (i.e., it will not be restricted to biological means), and be distinct from “agricultural bioterrorism” which will be defined as: the use or threatened use of disease inducing pathogens on agricultural targets, directed against victims selected for their symbolic or representative value, as a means of instilling anxiety in, transmitting one or more messages to, and thereby manipulating the attitudes and behavior of a wider target audience or audiences.

By late 1999, the threat of agricultural bioterrorism began to receive widespread attention for the first time in Congress. Over the following seven years, Congress held five hearings on agricultural bioterrorism or agricultural biosecurity.37 Ultimately, the hearings and heightened threat awareness led to the creation of new legislation directed at protecting not only historically identified critical infrastructure, but also agriculture. Passed on October 26, 2001 in the immediate wake of 9/11, the ‘‘Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism (USA PATRIOT ACT) Act of 2001’’ set forth a mission to “deter and punish terrorist acts in the United States and around the world, to enhance law enforcement investigatory tools, and for other purposes.”38 While not specifically naming agricultural bioterrorism, the law expanded the biological weapons statute (Chapter 10 of title 18, United States Code) which agricultural bioterrorism falls under, and dramatically loosened former legal restraints on federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies for the purpose of preventing future terrorist attacks.39

The first major legislation that named and aimed to protect agriculture against terrorism was signed into law on June 12, 2002, and was called The Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 (commonly referred to as the Bioterrorism Response Act).40 The law was passed in order to provide “regulation of certain biological agents that have the potential to pose a severe threat to both human and animal health, to animal health, to plant health, or to animal and plant products.”41 Important to the protection of the agriculture industry in this legislation was its subsection B, which is referred to as the “Agricultural Bioterrorism Protection Act of 2002.”42 This section enumerated protections to include the creation of a select agent and toxin list for enforcing protections. The law states that the “Secretary of Agriculture shall by regulation establish and maintain a list of each biological agent and each toxin that the Secretary determines has the potential to pose a severe threat to animal or plant health, or to animal or plant products.”43 The law also “necessitates that individuals possessing, using, or transferring agents or toxins deemed a severe threat to public, animal or plant health, or to animal or plant products notify either the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) or the Secretary of the Department of Agriculture (USDA).”44 In accordance with the Act, rules and regulations were published under the Code of Federal Regulations detailing the requirements for possession, use, and transfer for select agents and toxins. Pursuant to the law, sections 42 CFR Part 72 and 73 (published by HHS) and 7 CFR Part 331 and 9 CFR Part 121 (published by the USDA) are of significance.45

Passed on November 25, 2002, the Homeland Security Act of 2002 set into motion one of the largest reorganizations of government in U.S. history, and formed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).46 The resulting reorganization changed responsibilities for protecting agriculture. Specifically, it moved “personnel and responsibility for agricultural border inspections from USDA to DHS (specifically, from the USDA-Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to DHS Customs and Border Protection (CBP)).”47 Additionally, it moved the responsibility of operating, the now shuttered, Plum Island Animal Disease Center in New York from USDA to DHS.”48

Another source of policy involving the protection of agriculture has been homeland security presidential directives. The Homeland Security Presidential Directive 7 (HSPD-7), handed down on December 17, 2003 replaced “the 1998 Presidential Decision Directive 63 (PDD-63) that omitted “agriculture and food” in its coverage of critical infrastructure.49 According to the directive, HSPD-7 “establishes a national policy for Federal departments and agencies to identify and prioritize critical infrastructure and to protect them from terrorist attacks.”50 HSPD-7 identifies agriculture and food (meat, poultry, egg products) as critical infrastructure sectors and places their protection under the USDA.51

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 9 (HSPD-9) states that its purpose is to establish “a national policy to defend the agriculture and food system against terrorist attacks, major disasters, and other emergencies.”52 It highlights that at present, the “United States agriculture and food systems are vulnerable to disease, pest, or poisonous agents that occur naturally, are unintentionally introduced, or are intentionally delivered by acts of terrorism.”53 Bluntly, it also notes that “America’s agriculture and food system is an extensive, open, interconnected, diverse, and complex structure providing potential targets for terrorist attacks” and if exploited, “could have catastrophic health and economic effects.”54 To meet these challenges, HSPD-9 “generally instructs the Secretaries of Homeland Security (DHS), Agriculture (USDA), and Health and Human Services (HHS), the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Attorney General, and the Director of Central Intelligence to coordinate their efforts to prepare for, protect against, respond to, and recover from an agroterrorist attack” while “instructing agencies to develop awareness and warning systems to monitor plant and animal diseases, food quality, and public health through an integrated diagnostic system.”55 It also mandates that “response and recovery plans are to be coordinated across the federal, state, and local levels.”56

Homeland Security Presidential Directive 10 (HSPD-10), known as Biodefense for the 21st Century, came down in April 2004. Concerned with new bio-technology, the dual nature of the bio-threat, and the increasingly widespread know-how in life sciences, HSPD-10 set into motion greater efforts to prevent and control the threat of biological weapons.57 Food and agriculture were included in critical infrastructure and identified as potential targets.58

The National Response Plan, which has since been supplanted by the National Response Framework, was created in December 2004 as an “all-discipline, all-hazards plan that establishes a single, comprehensive framework for the management of domestic incidents” which coordinates “Federal support to State, local, and tribal incident managers and for exercising direct Federal authorities and responsibilities” while assisting “in the important homeland security mission of preventing terrorist attacks within the United States; reducing the vulnerability to all natural and man-made hazards; and minimizing the damage and assisting in the recovery from any type of incident that occurs.”59 Pertinent to agriculture is Emergency Support Function (ESF) #11 – Agriculture and Natural Resources Annex. ESF #11 states that it:

“…supports State, tribal, and local authorities and other Federal agency efforts to provide nutrition assistance; control and eradicate, as appropriate, any outbreak of a highly contagious or economically devastating animal/zoonotic (i.e., transmitted between animals and people) disease, or any outbreak of an economically devastating plant pest or disease; ensure the safety and security of the commercial food supply; protect natural and cultural resources and historic properties (NCH) resources; and provide for the safety and well-being of household pets during an emergency response or evacuation situation. ESF #11 is activated by the Secretary of Homeland Security for incidents requiring a coordinated Federal response and the availability of support for one or more of these roles/functions.”60

The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act, which passed November 27, 2006, came about as an expansion of existing penalties for the interference of the animal enterprise through acts of terrorism. The act states its purpose is to “provide the Department of Justice the necessary authority to apprehend, prosecute, and convict individuals committing animal enterprise terror.”61 The Bioterrorism Preparedness Act did not contain sufficient penalties for animal enterprise terrorism.62

As the principal organization tasked with protecting U.S. agriculture, the USDA has subordinate agencies which are responsible for carrying out specific missions towards this end. The Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is the chief agency in charge of monitoring and protecting crops and livestock from pests and diseases, as well as responding to emergencies resulting thereof. Put simply, the mission of APHIS is to “protect the health and value of U.S. agricultural, natural, and other resources.”63 Within APHIS there are six operational programs units, three management support units, and two offices supporting federal government-wide initiatives.”64 Three of the six operational program units within APHIS, International Services and Trade Support Team (IS), Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ), and Veterinary Services (VS), directly protect the U.S. from threats to agriculture.

IS focuses on threats that emanate beyond U.S. borders by providing “international animal and plant health expertise” abroad in order to “safeguard American agricultural health and promote U.S. agricultural trade.”65 Domestically, PPQ oversees threats against crops while VS protects against threats to livestock. Accordingly, their missions are to safeguard “agriculture and natural resources from risks associated with the entry, establishment, or spread of pests and noxious weeds” and to protect and improve “the health, quality, and marketability of our nation’s animals, animal products, and veterinary biologics by preventing, controlling, and/or eliminating animal diseases, and monitoring, and promoting animal health and productivity,” respectively.66

Also within the USDA, there are networks of laboratories created to “protect against animal, plant, food, and general bioterrorism issues.”67 The main purpose of these networks are to identify and detect “deliberate or accidental disease” outbreaks.68 The networks are organized under the National Plant Diagnostic Network (NPDN) and the National Animal Health Laboratory Network (NAHL). The NPDN, stood up by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), formerly the Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service (CSREES), is a network led by five regional labs and one support lab at Cornell University, University of Florida, Michigan State University, Kansas State University, University of California at Davis, and Texas Tech University (supporting) with the objective of establishing “a functional national network of existing diagnostic laboratories to rapidly and accurately detect and report plant diseases of national interest, particularly those pathogens that have the potential to be intentionally introduced through bioterrorism.”69

The NAHL is a collaborative effort between APHIS, NIFA , and the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians (AAVL).70 The network consists of laboratories which “focus on different diseases, using common testing methods and software platforms to process diagnostic requests and share information.”71 The USDA’s National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) at the federal level and state university laboratories work together to “perform routine diagnostic tests for endemic animal diseases as well as targeted surveillance and response testing for foreign animal diseases.”72 All with the goal of adding “support of routine and emergency animal disease diagnosis” to include bioterrorism incidents.73 Of importance, but outside of the USDA and still working towards detecting and diagnosing outbreaks of disease are: the CDC-led Laboratory Response Network (LRN) and the joint Food and Drug Administration (FDA)/Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) Food Emergency Response Network (FERN).74

DHS is the primary cabinet-level department responsible for protecting the homeland against threats of terrorism. In terms of preventing acts of agricultural bioterrorism, DHS’s Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and Customs and Border Protection Agriculture Specialists (CBPAS), are on the front line. The USDA-APHIS handed responsibility for agricultural inspection at ports of entry over to CBP upon the creation of DHS in 2003 (“approximately 1,573 agriculture specialists transitioned from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to CBP”).75 The transition has taken time, but APHIS and CBP continue to work together towards safeguarding agriculture.

Among APHIS’s many responsibilities, it develops regulations, policies, and operational guidelines for CBP, as well as, managing data collection and analysis setting performance measurements, managing preclearance programs, and generally, communicating policy with CBP.76 CBP then takes policies created by APHIS and enforces them with its 2,300 CBPAS working at 167 of the 300 ports of entry to the U.S.77 Additionally, CBPAS receive eight weeks of training and instruction from APHIS instructors prior to taking positions at ports of entry.78 Adding yet another layer of protection, CBPAS cross-train other CBP officers to enhance and extend agricultural knowledge amongst as many officers manning ports of entry as possible.79 Generally speaking, it is the CBPAS mission to identify any “item that might introduce a pest or disease into the United States.”80 In the course of their work, they “inspect shipments of imported products and ensure that the required permits, sanitary certificates (for animal products), and phytosanitary certificates (for plant products) accompany each shipment.”81

With over a trillion dollars in annual economic activity, protecting the agriculture industry in the U.S. has become a major priority for CBP. Every year, around $136 billion of crops are lost due to invasive species alone, most of which come through ports of entry.82 In an effort to mitigate this and the threat of introducing animal and plant disease, CBP intercepted 15,100 animal by-products, 392,149 meat products, and 1,212,526 plant material/soil products for a total of over 1.6 million intercepted products in 2012 that risked the U.S. agriculture industry.83 Assisting CBPAS in the identification and seizure of potentially harmful products are 118 canine teams.84

Another area working towards the protection of the agriculture industry under DHS is the Science & Technology Directorate Centers of Excellence (COE) network. The COE network consists of hundreds of universities working on the development of “new technologies and critical knowledge.”85 Among the twelve current centers of excellence, the Center of Excellence for Zoonotic and Animal Disease Defense (ZADD), works on programs aimed at protecting livestock. ZADD is spearheaded by Texas A&M University and Kansas State University with the aim of protecting “the nation’s agricultural and public health sectors against high-consequence foreign animal, emerging and zoonotic disease threats.”86

Mandated by HSPD-7, the National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP), identifies critical infrastructure and key resources and “sets forth a comprehensive risk management framework” with “clearly defined roles and responsibilities” for the Department of Homeland Security, Federal Sector-Specific Agencies, in addition to other Federal, State, regional, local, tribal, territorial, and private sector partners implementing the NIPP.”87 NIPP states that its overarching goal is “to build a safer, more secure, and more resilient America by preventing, deterring, neutralizing, or mitigating the effects of a terrorist attack or natural disaster, and to strengthen national preparedness, response, and recovery in the event of an emergency.”88 Food and Agriculture (FA) makes up one of the eighteen identified critical infrastructure sectors.

Each sector is overseen by a Sector-Specific Agency (SSA) which is “responsible for developing and implementing a Sector-Specific Plan (SSP), in collaboration with public and private sector partners, and for encouraging the development of appropriate information-sharing and analysis mechanisms.”89 For the FA Sector, the USDA is the SSA. Under the SSP, the Food and Agriculture Government Coordinating Council (FAGCC) and Sector Coordinating Council (FASCC), both formed in 2004, jointly hold quarterly meetings which facilitate a public-private forum for effectively coordinating agriculture and food protection “strategies and activities, policy, and communications across the sector to support the Nation’s homeland security mission.”90

The Strategic Partnership Program Agroterrorism (SPPA), similar to NIPP, is a government-private sector partnership program. Working together, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), DHS, USDA, FDA, as well as State, local, and industry partners strive to protect the U.S. food supply.91 The goal of the multi-actor partnership is to “collect the necessary data to identify sector-specific vulnerabilities, develop mitigation strategies, identify research gaps and needs, and increase awareness and coordination between the food and agriculture government and industry stakeholders.”92 Through the assessments put out by the SPPA, it is able to meet the requirements set forth by NIPP, SSP, and HSPD-9.93

Each state has its own department of agriculture that enforces state-wide laws and policies for agriculture. The laws and policies vary from state-to-state, but they tend to work towards the overall goal of securing crops and livestock from existing and potential threats. State departments of agriculture (SDA) serve as integral parts of overall agricultural biosafety. Due to their proximity to local farmers and ranchers, SDA not only have the ability to detect and react to potential acts of agricultural bioterrorism, but are also in the best position to prevent such acts.

In general, the purpose of a vulnerability analysis is to identify and prioritize vulnerabilities within a system, in this case, the agriculture industry. When assessed in conjunction with a threat analysis, the identification and prioritization of potential actors based on, among other things, ideology, motivation, and capacity, effective recommendations towards protecting the system can be made. The greater the specificity when identifying vulnerabilities, the easier it will be to ultimately make recommendations on hardening or protection from threats. While a much more nuanced study or series of studies should be conducted in order to make more specific recommendations, this threat assessment is surficial and intended only as an overview of the threat environment and is by no means exhaustive or comprehensive.

This vulnerability analysis will first make a target assessment based on historical cases of agroterrorism and threats thereof, as well as wartime use of bio-agents against agriculture and state-run biological weapons programs. It will then take into account what has previously been identified as vulnerable, as well as what is likely to be targeted based on economic and symbolic significance. Next the target vulnerability assessment will take the targets found in the target assessment and identify to what extent the targets are exposed and vulnerable. In doing so, current safeguards will be reviewed in terms of integrity and availability. Where deficient, the extent to which safeguards can or should be improved will be assessed. It is important to note that not all potential targets can or should be hardened. All hardening exacts costs, and these costs often impose operational constraints which adversely impact the bottom line for operators within an industry. Care must be taken to ensure that recommendations are holistic and consider all market factors. Lastly, there will be a vulnerability rating which summarizes the findings of the vulnerability analysis.

Acts of terrorism that have targeted agriculture have historically been relatively rare when compared to other means of terrorism. Perhaps the earliest reported incident of agroterrorism in the U.S. occurred in Ashville, Alabama in 1970 when a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan reportedly contaminated the water supply of a farm owned and operated by Black Muslims with cyanide resulting in the death of thirty cattle.94 On January 3, 1997, Purina, a large livestock feed products company, was forced to stop a shipment of 300 tons of feed after the feed was found to have been deliberately contaminated with chlordane, an extremely toxic and persistent insecticide.95 As an extension of the agriculture industry, likely the most recognizable act of terrorism involving food occurred when the Rajneeshee cult carried out a highly publicized act of bioterrorism in September 1984, which targeted the food industry. Seeking to disrupt a local election, members from the Rajneeshee cult in The Dalles, Oregon deliberately contaminated salad bars in ten restaurants and one grocery store with the pathogen Salmonella typhimurium, resulting in at least 751 cases of salmonellosis.96

Clear examples of agroterrorism outside of the U.S. have also been rare. In 1997, it was reported that Israeli settlers sprayed Arab grapes, south of Bethlehem, with a chemical causing the ruin of hundreds of grapevines and upwards of 17,000 metric tons of grapes.97 News sources also reported another incident near Bethlehem in 2000 where Israelis repeatedly released wastewater on fields owned by Palestinian farmers with the intention of forcing the Palestinians off the land.98

More common have been threats of agroterrorism, and a frequent tactic therein has been the issuance of threats through the mail. One such example came when The Breeders, a previously unknown entity, mailed letters to Los Angeles Mayor, Tom Bradley, in 1989 threatening to release Medflies (Ceratitis capitata), an invasive fly known for devastating fruit crops that it had been breeding.99 Interestingly, there are some indications that the attack may have been carried out as there were abnormalities in Medfly populations in southern California that year.100 The state Premier of Queensland, Australia received a letter threatening the inoculation of wild pigs with Foot-and-mouth disease in 1984.101 The office of New Zealand’s Prime Minister received a letter on May 10, 2005 claiming that Foot-and-mouth disease had already been released, and that more would be released if the author’s political demands were not met.102 Elsewhere, both the Ugandan and Sri Lankan governments had to manage threats against agriculture issued by the Ugandan People’s Passive Resistance Front in 1977 and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam between 1983 and 1987 respectively.103

Wartime usage of agricultural bio-agents have been more prevalent than cases of agroterrorism and agricultural bioterrorism, but it still remains relatively rare. During World War I, the German secret service carried out a agricultural bio-attacks against Argentina, France, Romania, the U.S., and the U.K.104 Specifically, the Germans targeted pack animals, cattle, sheep, and grain with, among other pathogens, Pseudomonas mallei (Glanders), Bacillus anthracis (Anthrax), and wheat fungus.105 In World War II, the Japanese used morbilliviruses (a group of paramyxoviruses which cause measles, rinderpest, canine distemper, etc.), Bacillus anthracis (Anthrax), and many other biological agents against the Soviet Union in northern China.106 Moreover, the Japanese used Yersinia pestis (Plague) infected fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) against the Chinese population and experimented with the targeting of cattle with fleas.107 There is also some evidence that may suggest that the Germans targeted British crops with Colorado potato beetles during the war. However, there is the possibility that the destructive beetle was introduced accidentally through the importation of of foodstuffs from the U.S.108

During the post world war era, there were also uses of biological agents against agriculture. For example, in 1952, the Mau Mau, a Kenyan nationalist liberation movement, used African milk bush (Sphagnum compactum) to poison thirty-three head of cattle at a British mission.109 The Cold War brought on many more reported uses.

The most famous was the alleged use of mycotoxins, called yellow rain, against the H’mong people by communist forces. The allegation held that the communist forces used aircraft mounted with sprayers in addition to mortars, grenades, rockets, and landmines to disseminate agents.110 Much debate remains as to the veracity of intentional usage. The toxins not only impacted crops and undermined confidence in local food stores, but also resulted in many deaths. The Soviet Union was also fingered in the use chemical and biological weapons later in the Soviet War in Afghanistan. While there was no way to say which agents were specifically used, due to the delay in sample collection, many villages and crops were impacted in the Soviet anti-agriculture campaign. Similar to the “yellow rain” allegations in Laos, some believe that the Soviets used trichothecene mycotoxins in Afghanistan.111 Soviet defector and former deputy director at Biopreparat, Ken Alibek, has stated that the Soviet Union utilized Pseudomonas mallei (Glanders) among other bio-agents to impact Afghan agriculture and human populations during the war.112

From 1962 through 1997, Cuba has accused the U.S. no fewer than twenty-one times of conducting biological warfare against its people and agriculture.113 “According to Raymond Zilinskas, the Cubans have alleged that the U.S. biological attacks caused ailments such as Newcastle disease among poultry (1962), African swine fever among pigs (1971, 1979-80), tobacco blue mold disease (1979-80), sugarcane rust disease (1978), dengue hemorrhagic fever among humans (1980), and an infestation of the thrips insect in 1996.”114 Despite the allegations, the most likely explanation is that the various outbreaks of disease were either the result of accidental importation or natural manifestations.

A good place to start when assessing which biological agents would potentially be the most desirable/feasible for terrorists, is known or suspected state-run biological weapons programs. Seeing what was researched and what was able to be weaponized should provide clues. Fifteen in total, states with former, suspected, or likely programs include: Canada (1941-1960’s), Egypt (1972-present), France (1939-1972), Germany (1915-1917; 1942-1945), Iraq (1980’s; 1990’s), Iran (1980’s-unknown), Israel (1948-present), Japan (1937-1945), North Korea (unknown-present), Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) (1978-1980), South Africa (1980’s-1993), Syria (unknown-present), United Kingdom (1937-1960’s), United States (1943-1969), USSR (Russia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan) (1935-1992; unknown).115

It is important to note that those states which are designated as still or possibly having programs are not done so due to state acknowledgement or can necessarily be confirmed by outside analysis with open source information. Rather, they are states that analysts assess to have biological weapons programs based on numerous factors. States with suspected programs include: Egypt (probable due to latent capabilities), Iran (uncertain), Israel (uncertain), North Korea (probable), Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) (probable; some analysts believe that “government forces infected livestock to impoverish the rural black population during the last phase of the civil war.”), Syria (probable), and Russia (unclear).116

There are numerous agents that the aforementioned states weaponized over the past century. These agents, their respective diseases, and the disease classes include: Aflatoxin (a mycotoxin produced by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus fungi), African swine fever virus (African Swine Fever), Bacillus anthracis bacteria (Anthrax), Influenza A virus (Avian Influenza), Barley yellow streak mosaic virus (Barley Mosaic Streak), Botulinum toxin (a protein and neurotoxin produced by the Clostridium botulinum bacterium), Brown grass mosaic fungus (Brown Grass Mosaic), Brucella bacteria (Brucellosis), Camelpox virus (Camelpox), Vibrio cholerae bacteria (Cholera), Mycoplasma mycoides subspecies mycoides Small Colony (SC) type bacteria (Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia), Orf virus (Contagious Ecthyma sheep), Eastern equine encephalitis virus (Eastern Equine Encephalitis), Foot-and-mouth disease virus (Foot-and-mouth disease), Fowl plague virus (Fowl Plague), Burkholderia mallei bacteria (Glanders), Phytophthora infestans oomycete (Late Blight of Potato), Corn Rust, Newcastle disease virus (Newcastle disease), Potato virus, Chlamydophila psittaci bacteria (Psittacosis), Piricularia oryzae fungus (Rice Blast), Helminthosporium oryzae (Brown Spot of Rice), Ricin (a toxin found in the seeds of the castor oil plant, Ricinus communis), Rinderpest virus (Rinderpest or Cattle Plague), Rye Blast, Salmonella bacteria, Tobacco mosaic virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus (Venezuelan equine encephalitis), Vesicular stomatitis virus, Western equine encephalitis virus (Western Equine Encephalitis), Wheat blast fungus, Wheat fungus, Wheat mosaic streak fungus, and Wheat stem rust fungus.117

Another area which can shed light on the feasibility of various pathogens for agricultural bioterrorism use are reputable science journals. With regards to crops, the Molecular Plant Pathology journal has published three separate articles which surveyed international experts in plant mycology, bacteriology, and virology. The articles highlight the top ten fungi, bacterias, and viruses based on worldwide scientific and economic importance. According to the survey on fungi, the top ten fungal plant pathogens are: Magnaporthe oryzae (Rice Blast), Botrytis cinerea (Gray Mold or Botrytis Bunch Rot), Puccinia spp. (Wheat Rust), Fusarium graminearum (Fusarium Head Blight), Fusarium oxysporum, Blumeria graminis (Barley Powdery Mildew or Corn Mildew), Mycosphaerella graminicola (Septoria Leaf Blotch), Colletotrichum spp. (Strawberry Anthracnose), Ustilago maydis (Corn Smut), and Melampsora lini (Rust of Flax or Rust of Linseed).118 The top ten bacterial pathogens impacting plants, according to the survey of bacteriological experts, are: Pseudomonas syringae pathovars, Ralstonia solanacearum (Bacterial Blight), Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Bacterial Wilt), Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Bacterial Blight of Rice), Xanthomonas campestris pathovars (Black Rot), Xanthomonas axonopodis pathovars (Bacterial Blight of Bean), Erwinia amylovora (Fire Blight), Xylella fastidiosa (Phoney Peach Disease), Dickeya (dadantii and solani), and Pectobacterium carotovorum (and Pectobacterium atrosepticum).119 Leading plant virologists listed the top ten plant viruses as: Tobacco mosaic virus, Tomato spotted wilt virus, Tomato yellow leaf curl virus, Cucumber mosaic virus, Potato virus Y, Cauliflower mosaic virus, African cassava mosaic virus, Plum pox virus, Brome mosaic virus, and Potato virus X.120

The U.S. government has also identified biological agents and toxins which it believes pose a threat to the U.S. agriculture industry (See table: USDA Select Agents and Toxins List). Per the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 and its mission of improving America’s “ability to prevent, prepare for, and respond to acts of bioterrorism and other public health emergencies that could threaten either public health and safety or American Agriculture,” HHS and the USDA published regulations (42 CFR Part 73 and 7 CFR Part 331/9 CFR Part 121 respectively) “detailing the requirements for possession, use, and transfer for select agents and toxins.121 According to the USDA, the Select Agent and Toxin List is based on the “effect of an agent or toxin on animal or plant health or products; the virulence of an agent or degree of toxicity of the toxin and the methods by which the agents or toxins are transferred to animals or plants; the availability and effectiveness of medicines and vaccines to treat and prevent any illness caused by an agent or toxin; and other criteria that the Secretary considers appropriate to protect animal or plant health, or animal or plant products.”122

| Livestock Pathogens | Plant Pathogens | USDA/HHS Pathogen Overlap |

|---|---|---|

| African horse sickness virus | Peronosclerospora philippinensis (Peronosclerospora sacchari) | Bacillus anthracis |

| African swine fever virus | Phoma glycinicola (formerly Pyrenochaeta glycines) | Bacillus anthracis Pasteur strain |

| Avian influenza virus | Ralstonia solanacearum | Brucella abortus |

| Classical Swine fever virus | Rathayibacter toxicus | Brucella melitensis |

| Foot-and-mouth disease virus | Sclerophthora rayssiae | Brucella suis |

| Goat pox virus | Synchytrium endobioticum | Burkholderia mallei |

| Lumpy skin disease virus | Xanthomonas oryzae | Burkholderia pseudomallei |

| Mycoplasma capricolum | Hendra virus | |

| Mycoplasma mycoides | Nipah virus | |

| Newcastle disease virus | Rift Valley fever virus | |

| Peste des petits ruminants virus | Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus | |

| Rinderpest virus | ||

| Sheep pox virus | ||

| Swine vesicular disease virus |

| Source: “Select Agent and Toxin List,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, last modified December 4, 2012, accessed November 18, 2013, http://www.aphis.usda.gov/programs/ag_selectagent/ag_bioterr_toxinlist.shtml. |

As was shown in the “Impact of Agriculture” section earlier in this paper, a relatively small number of crops and livestock represent enormous percentages of the overall agriculture industry in the U.S. Where crops are concerned, cash grains like corn, soybeans, and wheat hold a lot of value and are important not only in terms of domestic use, but also for export. Corn production alone is valued at $76.5 billion annually, while soybeans bring in another $35.8 billion and wheat makes $14.4 billion.123 Similarly, livestock and livestock products account for roughly half of the agriculture industry, but are spread across fewer products. The largest portion of the livestock sector is cattle which are currently valued at $100.7 billion.124 Other livestock and livestock products of significant value include: $39.7 billion in milk, $23.2 billion in broiler, $8.1 billion in hog and pig, $7.4 billion in egg, $5 billion in turkey, and $1.7 billion in chicken production.125 Thus, when considering potential targets based on economic or symbolic impact, leading grains and select livestock and livestock products should be noted.

Elbers and Knutsson state that while “agriculture may not be a terrorist’s first choice, because it lacks the shock value of more traditional terrorist targets, many analysts consider it a viable secondary target.”126 Historically speaking, they and the analysts they reference by and large would be correct. However, in the post-9/11 environment, which has been marked by unprecedented domestic antiterrorism and international counterterrorism efforts, would-be attackers may elect to bypass hardened targets altogether and focus on targeting easier to hit soft targets (e.g., the agriculture industry) in contrast to highly visible symbolic targets.

There are several factors that lend the agriculture industry to being particularly vulnerable to attack. First, as Elbers and Knutsson note, farms and ranches are geographically dispersed and cover expansive areas making security difficult, if not impossible.127 Moreover, livestock are typically held in close proximity and in high concentrations.128 Further exposing livestock is the fact that different populations of livestock are often commingled during transport and auction.129 Additionally, the “continuing trends of intensive production techniques, the vertical integration of the production continuum, increasing dependence on the export market, and the lack of resistance to pathogens that prevail in some countries are other factors contributing to the vulnerability of the livestock industry.”130 Importantly, should disease be intentionally introduced, given current agricultural practices, the consequences could be cascading.

When looking at agriculture post-harvest, there are even more opportunities to contaminate agricultural products. As stated by the former Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, Tommy Thompson, on December 3, 2004, “For the life of me, I cannot understand why the terrorists have not attacked our food supply, because it is so easy to do…We are importing a lot of food from the Middle East, and it would be easy to tamper with that.”131 Furthermore, the “farm-to-fork continuum” increases the vulnerability of the agriculture industry as a whole by increasing the number of potential avenues of attack and reducing the ability to prevent the introduction of pathogens before market.132 Indeed, the “production, processing, distribution, and preparation, has myriad potential vulnerabilities for natural and intentional contamination. Centralized food production and widened product distribution systems present increased opportunities for the intentional contamination of food.”133 With both pre and post harvest agricultural products widely vulnerable to attack, there are no shortage of opportunities for terrorists.

Assessing the vulnerability of a target and measuring to what extent it is susceptible to various forms of attack, many factors come into play. Pathogens that are relatively easy to find in the wild (i.e., they are prevalent and can be isolated with ease), can be safely handled, and can be easily cultured in a common medium pose the greatest threat to the U.S. agriculture industry. Dangerous bacterial pathogens pose a serious threat, but less so where they are zoonotic (i.e., they pose a threat to the health of a would-be handler) and not as abundant in the wild (i.e., they are less accessible to terrorists). Similarly, extremely virulent viral pathogens pose less of a threat, especially when they are zoonotic, due to the risks and technical requirements associated with handling, isolating, and weaponizing. What becomes important in figuring out which threats are most serious, is the intentions of potential terrorists in that the end goal will likely dictate the desired means.

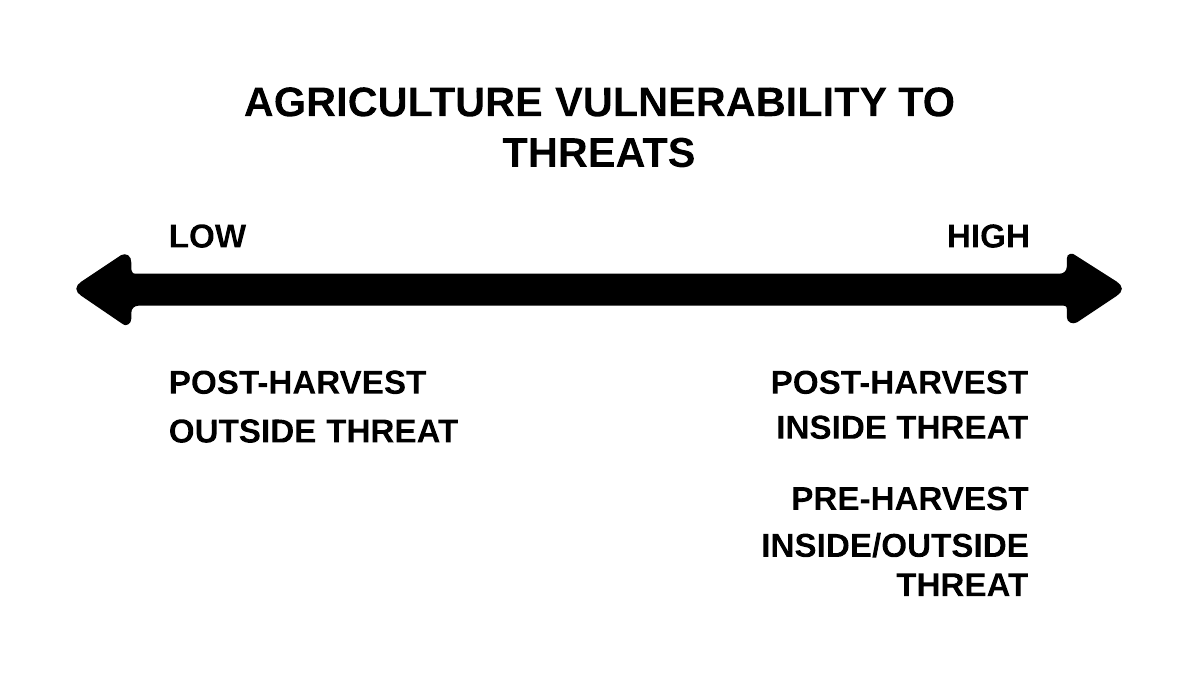

Currently, existing safeguards are generally in place to prevent accidental contamination and introduction of disease to crops and livestock. Additionally, the emphasis has been on protecting post-harvest agricultural products and products which are processed. This focus also needs to extend beyond processing. As stated by Dembek and Anderson, “When a product leaves the plant, that attention may be discontinued. The time and route of delivery, as well as the security of the transportation, may be the most important with reference to vulnerability and should not be overlooked when security planning.”134 To-date there are very few measures that would adequately prevent the intentional introduction of disease into pre-harvest crops and livestock. In place however, are surveillance programs that aim to detect disease early enough to prevent an outbreak and widespread losses. Their effectiveness in mitigating an outbreak of disease in the face of an intentional introduction remains untested.

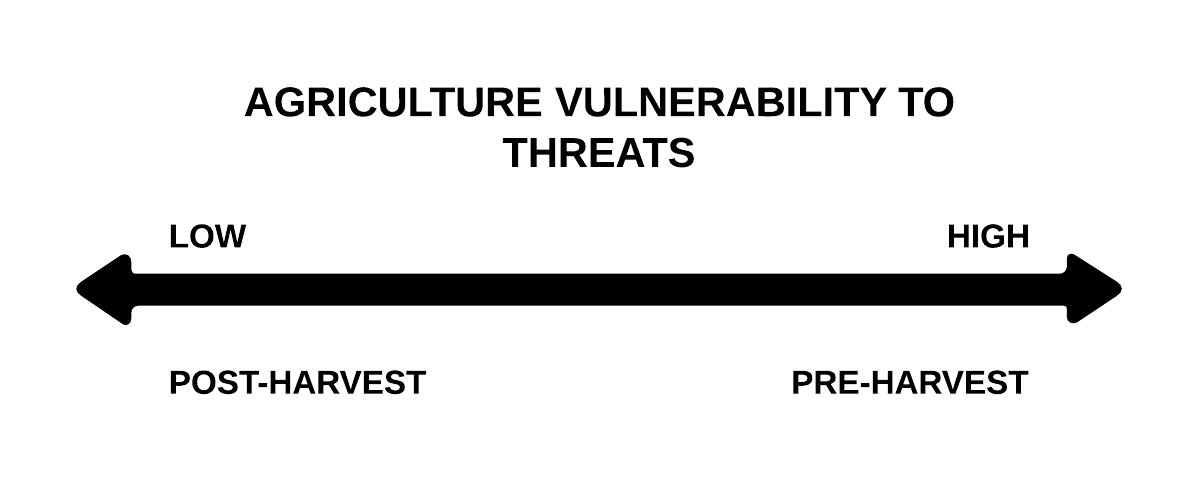

This vulnerability analysis has found that there are numerous vulnerabilities within the agriculture industry making it susceptible to agricultural bioterrorism. Additionally, there are a range of plant, animal, and zoonotic pathogens that could be utilized by terrorists. When looking at historic examples of threats, as well as state developed biological weapons programs, it becomes clear that important grains and livestock are prime targets.

Breaking agriculture into pre and post harvest, pre-harvest crops and livestock are least protected from attack. However, processed post-harvest agricultural products are also vulnerable, particularly after existing safeguards have been implemented (e.g., just prior to or during transportation).

Post-harvest agriculture is also more at risk from inside threats than outside threats given existing safeguards. Pre-harvest agriculture however, is only slightly more at risk to inside threats than to outside threats given its expansive and accessible nature.

The agriculture industry is most vulnerable to the deliberate introduction of pathogens which are virulent and cause disease in both crops and livestock while not infecting humans. This is because terrorists can handle these pathogens with ease and without the fear of self-infection. Moreover, pathogens which are easily obtained in the wild, but perhaps are no longer prevalent in the U.S., pose an enormous threat to U.S. agriculture. For example, taking a culture of Foot-and-mouth disease virus, not found in the U.S. but easily located in many developing countries, a terrorist could discretely import the culture with the intent to infect cattle with no risk to him/herself. Another example would be the deliberate introduction of the UG99, a relatively new and devastating race of stem rust fungus, into the U.S. Genetically engineered wheat families in the U.S. would not be protected and remain quite vulnerable.

The threat analysis will identify and prioritize potential terrorist actors based on, among other things, ideology, motivation, and capacity. The threat analysis includes a threat inventory, threat capacity, and threat rating. The threat inventory looks at the various types of terrorist groups and notes prominent organizations. Threat capacity, as the name suggests, takes the terrorist group typologies and specific terrorist organizations listed in the threat inventory and measures their capability and motivation to carry out an act of agricultural bioterrorism. Brought together, the threat analysis will then be coupled with the earlier vulnerability analysis to make recommendations for bolstering agriculture industry against agricultural bioterrorism.

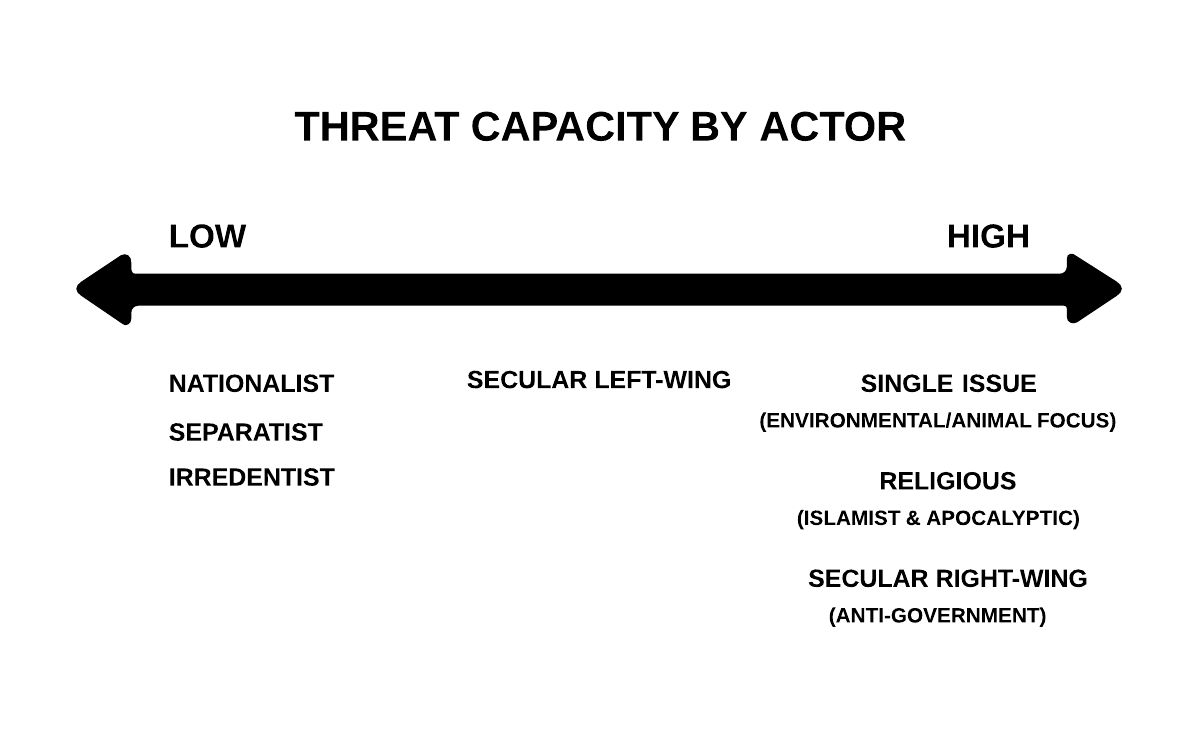

Non-state terrorist actors can be broken into five groups: nationalist, separatist, and irredentist groups; secular left‐wing groups; secular right‐wing groups; religious terrorist groups; and single‐issue groups. Nationalist, separatist, and irredentist groups are those which rely “heavily on terrorism that seek either to establish an independent state for the ethnic, linguistic, cultural, or national community with which they are affiliated, or (if they already have their own independent state) to unite all of the members of their community.”135 Notable terrorist organizations that have fit into this category include: Euskadi ta Askatasuna (ETA) or Basque Freedom and Fatherland, Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the Partiya Karkeren Kurdistan (PKK) or Kurdistan Worker’s Party, and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) also commonly referred to as the Tamil Tigers.136

While there are no designated nationalist, separatist, and irredentist terrorist organizations in the U.S., there are political organizations and loosely affiliated groups which promote and advocate independence and/or separation from the U.S. government. For example, there are groups seeking the independence of Alaska, Texas, Vermont, and Puerto Rico, as well as groups wanting to create new independent states like the Republic of Lakotah (consisting of parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana), Cascadia (comprised of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia), and New Afrika (a black nation consisting of southeastern states). Generally speaking, there are not calls to action that include violence, however, as with all political movements, there exists the potential for fringe actors to carry out acts of terrorism in order to try and get message resonance.

Secular left-wing groups are groups that rely “heavily on terrorism that seek to overthrow the capitalist system and either establish a “dictatorship of the proletariat” (Marxist‐Leninists) or, much more rarely, a decentralized, non‐hierarchical sociopolitical system (anarchists).”137 Well-known secular left-wing terrorist organizations have included Las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) or the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, Sendero Luminoso (SL) or Shining Path, Maoist organizations, Brigate Rosse (BR) or Red Brigades, and the Rote Armee Fraktion (RAF) or Red Army Faction, to name a few.138 There have also been a number of secular left-wing terrorist organizations in the U.S. The Weather Underground, May 19 Communist Organization (M19CO), and the Black Liberation Army (BLA), as well as Black and Puerto Rican nationalist groups have carried out acts of terrorism in the U.S.

Indeed, the vast majority of deaths, seventy-four percent, attributed to terrorism between 1988 and 1998 were at the hands of secular left-wing terrorist organizations.139 Of the domestic terrorist attacks in the U.S. during that time period, nearly half of the incidents were carried out by Puerto Rican separatist groups while the rest were carried out by more “traditional” leftist terrorist organizations.140 According to Seger, left-wing extremists are younger and better educated than are right-wing extremists, and tend to live in urban areas.141 Today, while fringe left-wing ideologies persist in the U.S., there has not been a preponderance of left-wing terrorism. This is largely due to the fact that state sponsorship of secular left-wing terrorist organizations has nearly ceased since the height of Soviet and Cuban sponsorship in the 1970’s and 1980’s.

Secular right-wing groups rely “heavily on terrorism that seek to restore national greatness (radical nationalists), suppress “subversive” opponents, expel or subordinate troublesome ethnic and cultural minorities (racists), or overthrow the existing democratic and “plutocratic” capitalist systems in order to establish a revolutionary “new order” (neo‐fascists).”142 As Masters states, “Right-wing extremists champion a wide variety of causes, including racial supremacy, hatred and suspicion of the federal government, and fundamentalist Christianity.”143 Important secular right-wing terrorist organizations have, among many, been: the Organisation de l’Armee Secrete (OAS) or Secret Army Organization, El Exército de Libertação Português (ELP) or the Portuguese Liberation Army, Los Grupos Antiterroristas de Liberación (GAL) or the Anti‐Terrorist Liberation Groups, La Alianza Anticomunista Argentina (AAA) or the Argentine Anti‐Communist Alliance, also known as the Triple A, and various militant groups in and across Latin America.144

In the U.S., while right-wing racism has been around for quite some time, and been represented by extremist organizations like the Klu Klux Klan, a new wave of racist organizations and movements, such as the Order and the neo-Nazi and Skinhead movements, began in the 1980’s. Also within the secular right-wing, the militia movement began to take root in the U.S. in the early 1990’s. At the time, this culminated with the 1995 bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City by Timothy McVeigh. This led to a massive crackdown by the federal government on militias and militia related activity. However, since 2008, the militia movement, and the broader patriot movement, have seen a massive resurgence in the U.S. The Southern Poverty Law Center emphasizes that “the number of conspiracy-minded anti-government “Patriot” groups reached an all-time high of 1,360 in 2012, while the number of hardcore hate groups remained above 1,000.”145 It was also speculated that “As President Obama enters his second term with an agenda of gun control and immigration reform, the rage on the right is likely to intensify.”146 DHS’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A) report that there is “no specific information that domestic right-wing terrorists are currently planning acts of violence, but right-wing extremists may be gaining new recruits by playing on their fears about several emergent issues. The economic downturn and the election of the first African American president present unique drivers for right-wing radicalization and recruitment.”147

Beginning in the mid-2000’s, other secular right-wing movements include the Minutemen movement and the Oath Keepers movement. Dubbed the Minutemen Project, the movement consists of right-wing individuals which seek to prevent illegal immigration. They self-describe themselves as the “neighborhood watch for the border.” Oath Keepers advocates that members of the military and law enforcement community uphold their oath to “defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” Emphasis within this movement has been placed on protecting the Constitution from what are seen as domestic threats (i.e., the Federal government) to the Constitution.

Religious terrorist groups use terrorism seeking “to smite the purported enemies of God and other evildoers, impose strict religious tenets or laws on society (fundamentalists), forcibly insert religion into the political sphere (i.e., those who seek to “politicize” religion, such as Christian Reconstructionists and Islamists), and/or bring about Armageddon (apocalyptic millenarian cults).148 Religious groups can be further subdivided into the following categories: Islamist terrorism; Jewish fundamentalist terrorism; Christian terrorism (fundamentalist terrorism of an Orthodox, Catholic, or Protestant and Christian Identity); Hindu fundamentalist and nationalist terrorism; and apocalyptic religious cult terrorism.149 Religious terrorist organizations of significance include: al‐Qa`ida (the Base); Hizballah (Party of God); al‐Harakat al‐Muqawwama al‐Islamiyya or HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement); al‐Jihad al‐Islami (Islamic Jihad); the Groupe Islamique Armé (Armed Islamic Group) and Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (Salafist Group for Preaching and Fighting); Jemaah Islamiyah (Islamic Community); Abu Sayyaf Group; and the U.S. group, Phineas Priesthood and the Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord.150 Of the religious terrorist organizations, the greatest threats emanate from al-Qa’ida, affiliated movements, and their adherents.

Single-issue groups use “terrorism that obsessively focus [sic] on very specific or relatively narrowly‐defined causes of various sorts.”151 “This category includes organizations from all sides of the political spectrum, e.g., animal rights groups such as the Animal Liberation Front (ALF); anti‐communist groups such as the Cuban exile organization Omega 7, the Comando de Caça aos Comunistas (CCC: Communists‐Hunting Commando) in Brazil, and the [Grupos] Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC: United Self‐Defense Groups of Colombia); and anti‐abortion groups such as the Army of God (AOG) in the United States.”152 Another organization that falls under single issue is the Earth Liberation Front (ELF). Prior to 9/11, it was seen as the single greatest terrorist threat to the U.S. homeland by the FBI. “…special interest extremism–as characterized by the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and the Earth Liberation Front (ELF)–has emerged as a serious terrorist threat. The FBI estimates that ALF/ELF have committed approximately 600 criminal acts in the United States since 1996, resulting in damages in excess of 42 million dollars.”153

When looking at vulnerabilities and their level of exposure to threats, it is also helpful to separate the threats by whether they emanate from international terrorist organizations or domestic. It can be assumed that domestic terrorists would have a greater knowledge of the areas they operate than would an international actor whom may have very little experience living and working in the area. Another way of think about this, it is similar to the difference between internal and external threats. One actor has a vastly more intimate knowledge of the environment than does the other. It should be cautioned that in recent years, self-radicalized actors have been the most successful in terms of advancing along the attack spectrum (e.g., the Boston bombers). These “homegrown” terrorists have frequently operated in the name of, or under the influence and direction of, foreign terrorist organizations (e.g., the Time Square bomber, Faisal Shahzad). Such actors represent a very potent threat.

Broken up into nationalist, separatist, and irredentist groups; secular left‐wing groups; secular right‐wing groups; religious terrorist groups; and single‐issue groups, the threat inventory identified the types of terrorist organizations and noted prominent groups therein. The threat capacity will take these categories and look at motivation and capability to measure capacity.

There are no designated nationalist, separatist, and irredentist groups operating in the U.S. However, as was mentioned in the previous section, some fringe groups hold beliefs that align with this categorization. Motivationally speaking, if a group were to organize further, a more substantial threat could emanate. Separatist groups have carried out guerilla fights against states utilizing many tactics in the past. While it would be premature to speculate as to whether the existent groups in the U.S. or those that share sentiment would be motivated to carry out agricultural bioterrorism, it can be said that their capability would be on par with individual homegrown terrorists as there are no well-coordinated or structured groups operating in the U.S.

Secular left-wing groups have historically carried out violent attacks and posed a great threat in the U.S. during the height of the Cold War. That said, since the end of the Cold War and the cessation of state-sponsorship to disparate left-wing terrorist actors in the U.S., the threat has been largely reduced to individuals. Larger organizations like the U.S. Communist Party might sympathize with potential actors, but there are no designated left-wing terrorist organizations operating in the U.S. Agriculture could be a target to individual actors with leftist beliefs. Especially when viewed as a means to impact the U.S. capitalist economy. Capacity however remains low due to a lack of organization and absence of specific threats.

Secular right-wing groups pose a unique threat to agriculture. While members of the fringe left have tended to populate urban areas, right-wing members have gravitated towards rural areas. This puts them, generally speaking, in close proximity to much of the nation’s agriculture production. Motivation may vary with ring-wing individuals as some may have direct interests in the agriculture (e.g., they may work in the agriculture industry). However, if the aim is to take down the “corrupt” government, agricultural bioterrorism may be seen as a means to that end, and familiarity with agriculture lends heavily to this form of attack. Groups and individuals that fall under racist or issue based right-wing ideology (e.g., immigration) may be more inclined to target specific agriculture based upon who owns it than government focused groups. There is a higher degree of organization within this category than the preceding two, but the the threat is mostly from individual actors. Thus, the capacity to carry out agricultural bioterrorism varies widely.

Religious terrorist organizations pose a significant threat to agriculture. Specifically, al-Qa’ida, affiliated organizations, and their adherents have sufficient motivation and resolve to carry out an act of agricultural bioterrorism. To-date, al-Qa’ida has opted for attempting flashier attacks that exact a high number of casualties. However, with the enormous rise of antiterrorism infrastructure in the post-9/11 world, softer targets like agriculture are increasingly more likely to be targeted. Moreover, an agricultural bio-attack is fully consistent with al-Qa’ida’s modus operandi. Al-Qa’ida’s leader, Ayman al-Zawahiri, stated recently that “We [believers] should bleed America economically by motivating it to continue its huge expenditure on its security as America’s weak point is its economy…”154 Al-Qa’ida does not operate in large numbers in the U.S., but has, like actors in other categories, the potential to inspire individual or lone-wolf attacks. Indeed al-Zawahiri calls for such attacks. “These dispersed strikes can be carried out by one brother, or a small number of brothers.”155 Capability may be limited for foreign actors, but domestic actors will have much greater chances of successfully carrying out an attack. As such, the motivation is high and the capability is moderate. Thus, the capacity is fairly high.

Single issue terrorists cover a wide-range of beliefs. The greatest threats come from environment and animal focussed organizations. The Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) pose very real threats to the agriculture industry. As Executive Assistant Director of Counterterrorism and Counterintelligence at the FBI, Dale L. Watson highlights, “…special interest extremism–as characterized by the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and the Earth Liberation Front (ELF)–has emerged as a serious terrorist threat. The FBI estimates that ALF/ELF have committed approximately 600 criminal acts in the United States since 1996, resulting in damages in excess of 42 million dollars.”156 These organizations are motivated and capable. Therefore, they have a high capacity.

For the threat rating, a low rating can be given where the threat has little or no capability or motivation. A high rating can be given for those threats that are highly capable and highly motivated.

In April 2007, the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) stood up a joint agency task force (JATF) to evaluate and develop recommendations on how to better accomplish the agriculture inspection mission.157 The task force found thirteen categories of key issues, and action plans were drawn up to address the issues and implement corrective actions.158 The first area that needs to be improved according to the action plan is in the area of structure and leadership. It states that “the management and leadership infrastructure supporting the Ag mission from CBP should be staffed and empowered at levels equivalent to other functional mission areas in CBP.”159 Still needed is an evaluation of the management and support structure servicing CBP ports of entry, field offices, and headquarters in order to achieve optimum structure.160